Descrizione

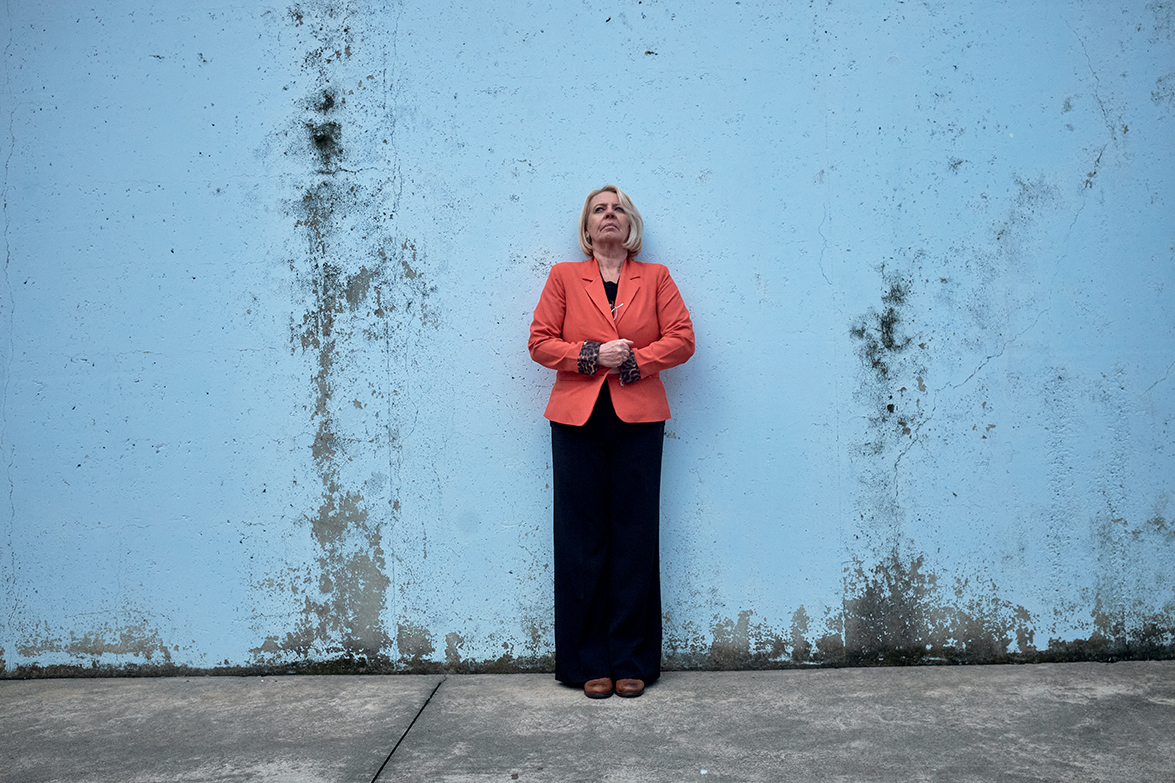

È una collezione di ritratti di donne in carcere realizzati da Giampiero Corelli negli ultimi due anni. Due incredibili anni di pandemia e restrizioni che hanno cambiato il nostro modo di vivere e di percepire l’idea stessa di libertà. Vulnerabili e impauriti, rinchiusi nelle nostre abitazioni, abbiamo osservato il mondo dalle finestre sperimentando la reclusione, sorpresi da un orizzonte sempre uguale.

Forse proprio questa esperienza collettiva d’isolamento e costrizione consente di attribuire un valore fortemente empatico alla realistica rappresentazione della reclusione raccolta in questo volume.

Corelli compie un viaggio in tredici istituti penitenziari femminili italiani – ultima parte di una lunga indagine iniziata più di vent’anni fa – realizzando fotografie e intense video interviste che sorprendono per la capacità di stare di fronte al dolore dell’altra. Senza incalzare, ascolta. Sono storie di donne assassine. Hanno ucciso per caso, per sbaglio. Si sono pentite e mai assolte. Tutte consapevoli di aver commesso un errore o tanti.

Ingannate da un sogno d’amore finito male. No, non era l’uomo giusto ma l’hanno seguito lo stesso. Pensavano cambiasse ma sono cambiate loro. E la droga, brutta bestia, in un attimo ti porta via e ti fa fare cose che non vorresti.

Fuori c’è il passato: figli lasciati e figli che le hanno ripudiate. In entrambi i casi il dolore taglia la carne, incide l’anima. Storie che si somigliano. Storie da immaginare oltre la periferia, dove la città sprofonda in luoghi senza nome, dietro ai muri perimetrali delle case circondariali, pensate per infliggere e costruite per privare.

L’autore entra nelle celle, raccoglie confessioni terribili di donne disarmate, consapevoli e sincere, che rivelano sogni e ammettono crimini. È consapevole che la sua presenza altera la scena ma la consuetudine nelle prigioni gli ha conferito un’abilità straordinaria nel rendersi invisibile, unico uomo, in un universo completamente femminile. Dedica la stessa attenzione alle guardie che in questa rappresentazione si confondono con le detenute rivelando l’aspetto migliore della detenzione: la relazione umana. Non ci sono buone o cattive ma semplicemente donne recluse: a ognuna la sua colpa, per tutte la costrizione. Nessun vezzo cinematografico, nessuna astuzia stilistica, sa scomparire e accogliere.

Domani faccio la brava è una concatenazione di immagini di singole donne, in cui si alternano volti scolpiti dal disagio e corpi costretti in uno spazio coatto. Recluse e promiscue, a piccoli gruppi o a coppie, il riscatto è la relazione. Si sbracciano, si abbracciano, si sfiorano, si soccorrono, ognuna conosce la pena.

Giampiero Corelli è un reporter, uno che trasforma le notizie in fotografie. È di quelli che stanno sul pezzo, abituati a partire appena c’è un lancio d’agenzia o la chiamata di un redattore.

È cresciuto nei quotidiani, ha iniziato al Messaggero e poi da quasi trent’anni è al Resto del Carlino. Non ha avuto maestri o mecenati. È un fotografo di mestiere che coltiva passioni. Affianca al lavoro quotidiano progetti a lungo termine con la dedizione di un decoratore, componendo pazientemente, per mesi o per anni, le tessere che costruiranno il mosaico di vite policrome di donne controcorrente. Tratteggiate da dolore, solitudine, riscatto e compassione, le eroine sono deejay, performer e cantanti romagnole che sposano il liscio e amano il rock, o badanti che gli affidano le loro storie invisibili. Se le suore di clausura sono state uno dei primi territori dell’indagine ai confini dell’insolito, è alle detenute nelle carceri italiane che dedica un impegno che non ha mai cessato di appassionarlo. Viaggiando lungo la penisola, ha perlustrato decine di istituti: una sorta di allenamento costante alla narrazione intima che corre parallelo alla sua vita professionale.

Le carceri femminili sono quindi la sua palestra creativa, l’occasione della conoscenza, il luogo delle relazioni e quasi un paradosso, la libertà del progetto.

L’incontro è il fulcro della ricerca, l’approdo della curiosità, in cui la fotografia esplora biografie sensibili e rivela mondi inaccessibili.

Ci sono esperienze, come quella di Giampiero Corelli, in cui si può rintracciare un rinnovato senso del fotogiornalismo, attraverso una straordinaria dedizione per i suoi soggetti e una vocazione alla mappatura tematica e geografica. Così l’autore restituisce una nuova vitalità a un linguaggio messo in discussione per le sue ambiguità, tornando alle origini di una fotografia spontanea capace di avvicinarsi alle persone per restituire la fisicità dell’incontro, la corporeità dell’esperienza. Non c’è mai una ricerca formale fine a se stessa, non si avverte l’esercizio di stile, poiché Domani faccio la brava è un’opera autentica, disarmante nella forma semplice del linguaggio, a tratti ingenua, profondamente onesta, maneggiata con disinvoltura.

Tutto il lavoro è pervaso da uno sguardo benevolo e assolutorio, ammantato di speranza, punteggiato da un’inaspettata allegria in cui sembrano risuonare voci che promettono: “Domani faccio la brava”.

Renata Ferri

Luglio 2022

Tomorrow I’ll Be Good

This book is a collection of portraits of women in prison taken by Giampiero Corelli over the past two years, two years of pandemic and restrictions that changed our way of living and perceiving the idea of freedom itself. Vulnerable and afraid, enclosed inside our living places, we watched the world from our windows, experiencing confinement, surprised by a seemingly unchanging horizon.

Perhaps it was precisely this collective experience of isolation and constriction that allows us to assign a strongly empathetic value to this book’s realistic representation of confinement.

Corelli carries out a journey through thirteen women’s prisons in Italy, the final part of an even longer journey that began more than twenty years ago, taking photos and conducting intense video interviews that are disarming for their ability to simply be in the presence of another’s pain. Without putting any pressure, just listening. These are stories of women who have taken lives. Some did so by accident, mistakenly. They have repented but they have never been absolved. Each one is aware of having made a serious mistake (or many).

Betrayed by a dream of love that ended badly. No, he wasn’t the right guy, but they stuck by him nonetheless. They thought he’d change but they were the ones who changed. And drugs, those cruel beasts, can take you away in a moment and make you do things you don’t want to do.

Outside there’s the past: children who were left behind and children who rejected them. In both cases, the pain cuts into the flesh, scarring the soul. The stories resemble each other. These are stories that took place at the outskirts of town, where the city descends into nameless places, beyond the walls marking the perimeters of district houses, designed to inflict and built to deprive.

The artist enters into their cells, gathers the terrible confessions of vulnerable, self-aware, and sincere women, who reveal their dreams and admit to their crimes. He is aware that, in their presence, he changes something about the setting, alters it, but the habit of visiting prisons has given him the extraordinary ability to make himself invisible, the only man in a completely female universe. He devotes the same attention to the guards who, in this collection, are mixed along with the prisoners, revealing the best, most redeeming aspect of detention: human relationships. There aren’t “good” or “bad” women, only women in confinement: to each one their faults, and to all of them constriction. Without any kind of cinematographic flourish, without any stylistic cunning, the artist knows how to disappear and also knows how to make his subjects feel welcome.

Tomorrow I’ll Be Good is a chain of images of women, one at a time, in which one witnesses a sequence of faces sculpted by discomfort and of bodies forced into a tight space. Presented in small groups or in pairs, their relationships with each other are their redemption. They embrace, touch, help each other, each one of them knows sorrow, punishment.

Giampiero Corelli is a reporter, someone who transforms news into photographs. He is one of those people who follows the story, who is used to setting off as soon as there is a press release or the call of an editor.

He was raised in the world of dailies, beginning with Il Messaggero and Il Resto del Carlino, where he has worked for almost thirty years. He has had neither teachers nor patrons. He is a photographer by trade, one who nurtures his passions. Alongside his reporting, he has pursued various long-term projects with the devotion of a decorator, composing patiently, for months or for years, the pieces that will eventually make up the mosaic of polychromatic lives of counter-current women. Marked by pain, solitude, redemption, and compassion, his heroines are DJs, performers, and singers of music in the dialect and tradition of the Romagna region, marrying traditional liscio with rock, or they are caregivers who lend him their invisible stories. Cloistered nuns were one of his first subjects, figures through whom he began his explorations of unique, unusual topics. But he exhibits a special commitment toward inmates in Italian prisons, a commitment that never ceases to thrill him. Traveling along the peninsula, he has scoured dozens of institutes: a sort of constant training in the intimate narrative that runs parallel to his professional life.

Women’s prisons are a space in which his creativity is exercised, an occasion for new forms of knowledge, new forms of relation, and, almost paradoxically, a space of creative freedom.

The place of encounter is the fulcrum of the project, the place where curiosity leads him, in which the art of photography explores sensible biographies and reveals inaccessible worlds.

There are experiences, like those of Giampiero Corelli, in which one can trace a renewed sense of photojournalism, through an extraordinary dedication toward its subjects and a special vocation for thematic and geographic mapping. In this way, the artist restores a new vitality to a language that had been questioned for its ambiguities, returning to the origins of a spontaneous form of photography capable of getting close to people in order to restore the physicality of the encounter, the corporeality of experience. It is never just a matter of form as an end unto itself, and it is not a merely stylistic exercise, for Tomorrow I’ll Be Good is an authentic work, disarming in the simplicity of its language, which is almost naive, profoundly honest, and handled with nonchalance.

The work as a whole is pervaded by a benevolent and absolving gaze, endowed with hope, and punctuated by an unexpected feeling of joy in which a chorus of voices seems to promise: “Tomorrow I’ll be good.”

Renata Ferri

July 2022